Traditional neuroscience tells us that our mental abilities peak during our late 20s, as our brain brain volume shrink and our mental capacity starts its decline. Renowned psychologist Timothy Salthouse spent years researching the subject of cognitive aging, testing more than 8,000 people in his lab at the University of Virginia. In the studies, he tested the memories, problem-solving skills, and other cognitive functions of subjects to see how how the brain functions as it ages.

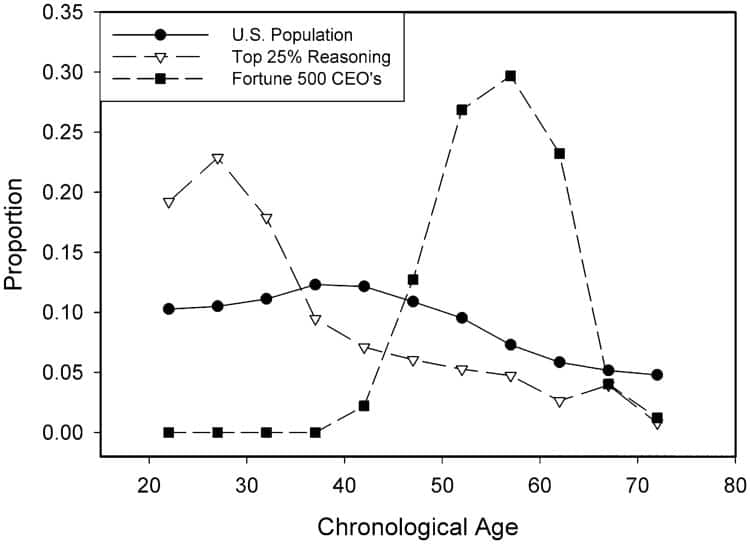

While some of the evidence seems to confirm traditional neuroscience, there were some oddities that became apparent as the data was mined. The study confirms a well-known scientific pedigree—the ability to reason peaks at the age of 28 for the general population and then goes into a downward spiral thereafter. But here’s the anomaly—-Salthouse found that for CEOs of Fortune 500 companies, overall cognitive abilities peak just before reaching the age of 60. About half of the CEOs are older than 55, and the number under 40 is about zero. But this dichotomy makes for a very interesting observation—mental abilities can increase as we age. The mental skills that fade in our 20s is made up with other mental abilities as we age.

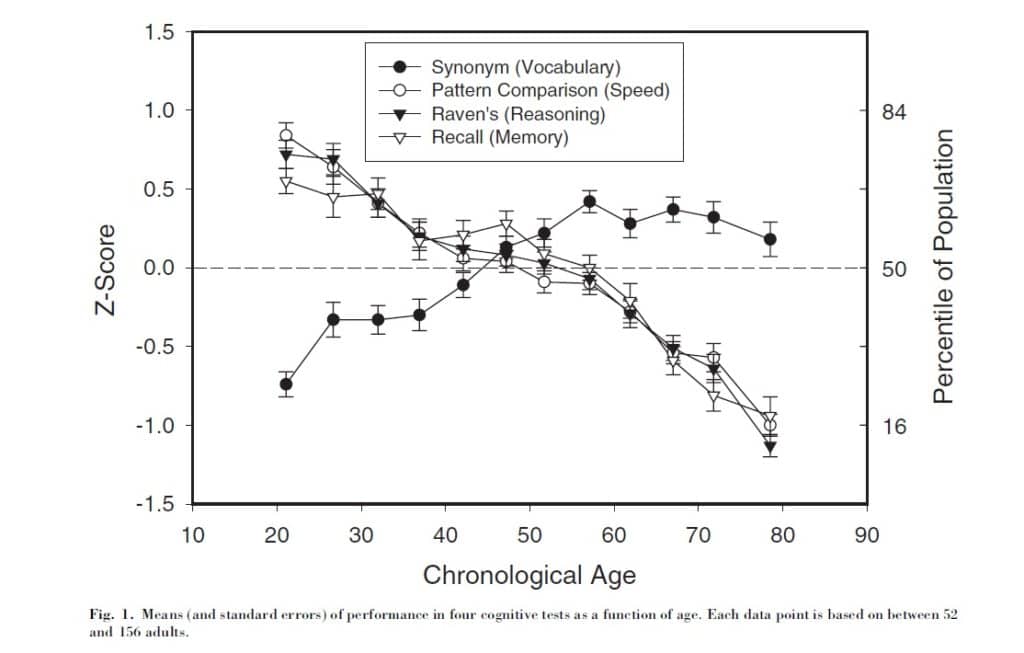

Here is the quick look at the results of Salthouse’s study:

As you can see, cognitive function such as speed, reasoning, and memory does decline in our late 20s. However, the test for vocabulary does seem to increase until reaching the 50s.

However, if you look at the next chart, you will see that overall cognitive abilities do not peak until they reach 60 for CEOs.

Questioning Earlier Studies on Brain Aging

Salthouse states that the traditional paradigm for thinking about cognitive development and brain aging needs to be retested because it has largely been based on empirical evidence, or flawed in other manners.

For instance, traditional science posits that brain volume begins to shrink as we get into our 30s. Studies of the past suggested that the prefrontal cortex has the greatest reduction in volume. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for executive function such as forethought, planning, reasoning, and overall fluid intelligence (the ability to apply logic and reasoning to solve novel problems). But as it turns out, the studies concluding this may have been skewed by a fraction of the sample size having early stage and largely asymptomatic dementia. Although largely asymptomatic, those with early stage dementia still experience a loss of volume in the prefrontal cortex. Had the sample size only contained truly healthy people, there might not be such volume loss.

Another claim that comes under question for Salthouse is earlier studies finding that fatty insulation around neruons (also referred to as myelination), peak in our late 20s and then further decline as we get older. Because myelin allows electrical signals to travel through the brain more quickly and efficiently, the loss of such would mean it takes longer to connect two items together, such as a face with a name or an actor with a movie. But Salthouse found that myelination loss is not global—its loss affects one specific part of neurons, the part that is responsible for learning new things. So it may indeed take a bit longer to learn new things. However, there is no myelination loss when it comes to the part responsible for long-term memory, a part of crystallized intelligence. And this maybe what accounts for our trouble with taking in new memories and information as we get older, but why we tend to retain much of our core memories and knowledge.

In Salthouse’s study, he points out that only 20 percent of the variation among people in standard measures of memory, problem-solving, and other executive functions is due to age. The rest is attributed to factors other than age. Many of the paradigms science has about brain aging comes from flaw conclusions from cross-sectional comparisons—getting a bunch of young people and old people together to compare their differences through as series of identical tests. But what cross-sectional studies fail to do is take into account generational differences. Over the last 30-40 years, much has happened that would influence the education, diet, and lifestyle of citizens that would warrant a change in the way the brain functions and how well it functions. And thus comparing the two generations fails to take into account other factors that may have affected the decline in cognitive abilities. When the same people are measured repeatedly, there is either a stability or an increase in brain function, at least before the age of 60.

Although the speed at which we learn new things slows as we past our 20s, it seems that many of our other mental abilities stay steady or even increase. In other words our fluid intelligence may begin to see a decline in our 20s. However, the ability to use and apply our knowledge, skills, and experience to solve problems does not peak in some until the age of 60. In other words, our crystallized intelligence peaks at the age of 60 for some of us. Our emotional intelligence, vocabulary, social skills, and self-control improve with age. There are many nobel laureates that are older than 60, thus proving that the pace at which the brain peaks and ages is wholly dependent on the person and their lifestyle choices throughout life. Those who are mentally active and constantly challenge their brains been to shown to hold up well when it comes to brain aging—with some even showing an increase in mental acuity with age. The new revolution in neuroscience and cognitive science has begun to question old methodology and axioms as they no longer stand up to scientific scrutiny.

Highlights from article:

- Processing speeds generally decline as we past our late 20s

- However, other mental abilities make up for our slower processing speeds

- Fluid intelligence may peak during our 20s but crystallized intelligence does not peak until the age of 60

- Previous studies into brain aging are flawed and need to be looked at again

- Generational differences in diet and lifestyle may attribute for the difference in brain age

- Difference in brain function may be affected by factors other than age

- The same thing that is good for your heart is what is good for your lungs. That means eating healthy and regular exercise to keep the immune system strong is essential to a healthy brain

Leave a Reply